Should I Switch From Git to Jujutsu

Jujutsu is a new version control system that is backward-compatible with Git. All the cool kids are raving about it. In this article I will try to help you decide whether it’s worth investigating.

If you use git rebase, the answer to this article’s question is probably yes.

You will mostly likely love Jujutsu.

Proceed to Part Two.

Do not pass Go.

Do not collect two hundred dollars.

If you don’t use git rebase, you might still enjoy Jujutsu, but you might wonder, why would I care about all this fancy stuff?

All I do with Git is commit and occasionally sync with main… what more could I possibly want?

Part One: Why Do I Care?

For solo personal projects, Jujutsu doesn’t have much to offer.

Just live your life and keep committing straight to main.

But if you work with other people, you probably have to deal with the hardest problem in computer science:

Code review is painful, whether you’re reviewing or being reviewed.

When reviewing a pull request with someone in Github (for example), you will see all the changes from all the commits in the pull request mashed together into one view, and sorted in alphabetical order by filename, like this:

file_afile_bfile_c

This is often confusing to read, because in reality, you might have modified the files in a different order:

file_bfile_cfile_a

To make the review go smoother, you might click into the individual commits and read them one at a time. But oftentimes, this doesn’t help much, because the commits look like this:

- Huge incomprehensible refactor

- Fix tests

- Appease linter

- Sync from main branch

- Address AI code review

- Sync from main branch

- Fix typo

- Add more tests

- Sync from main branch

- Sync from main branch

If you could curate your commits to tell a nice understandable story, you might get through code review a lot faster and easier.

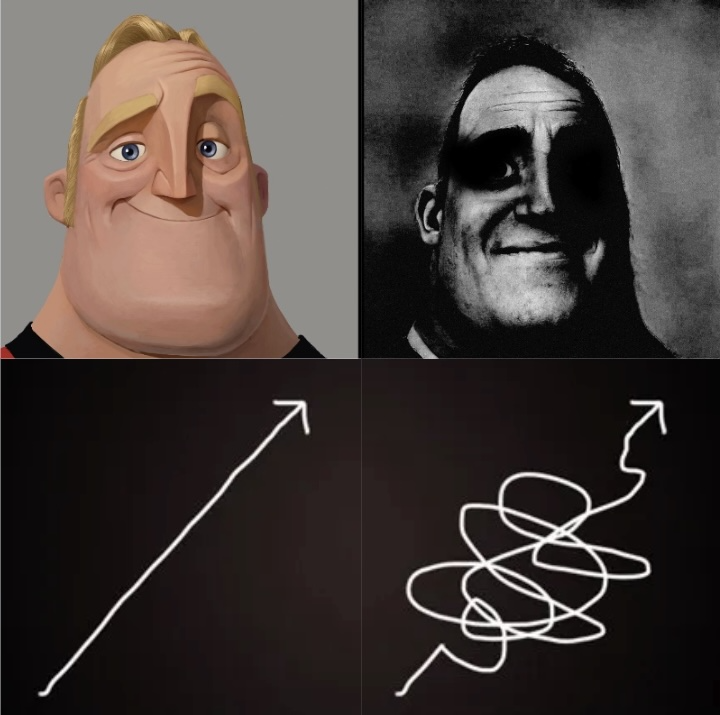

When someone reviews your code, your want each step to be straightforward and obvious, like you’re walking in a straight line from where you are to where you want to go. If you’ve seen commits like this, it feels like the author can predict the future.

You might read the first commit and think, “I don’t see how this relates to the task at hand.” But as you keep reading commits, it becomes clear why that first commit was necessary. It’s like the author presciently knew they would run into problems later on, so they had to make that change first. It’s a sight to behold.

The problem is, in reality, I can’t predict the future. And therefore, I don’t work in straight lines.

I get halfway through something and realize I need to change directions. I trade blows with linters. And the resulting squiggly line is much tougher to read and review.

So how can I get that beautiful straight line?

I rewrite history.

This is what git rebase does.

It allows you to rewrite history and make your commits understandable.

If all you do is commit and sync from the main branch, hopefully this makes it clear why you might be interested in a slightly fancier workflow. It makes code review less painful.

Part Two: Jujutsu Differentiators

The underlying data model of Git is beautiful and elegant, but the tools for manipulating it are notoriously unintuitive. Jujutsu aims to solve that.

Here are the main areas where Jujutsu diverges from Git. These didn’t make sense to me right away. I just let them wash over me and eventually they made sense as I absorbed the details.

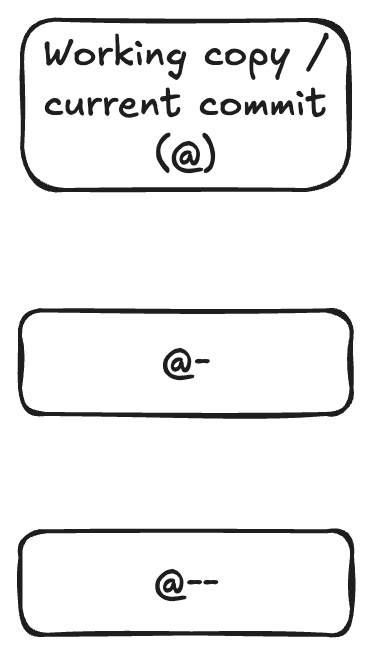

Everything is always committed. There’s no staging area in Jujutsu. You don’t pick and choose what things to commit. Everything is always saved into the current commit.

Commits are mutable. Since everything is automatically saved into the current commit, that commit will necessarily change over time. Jujutsu can even show you the history of how each commit has changed over time, a bit like the Timeline feature in VSCode.

You can undo! Have you ever messed up a Git repository so bad that you had to delete and redownload it? With Jujutsu you just type

jj undo. Version control has finally entered the 1960s. This alone is enough to make Jujutsu worthwhile.Rewriting history is a first-class citizen. This is the big one. In Jujutsu, you are constantly rewriting history by default. You do it without realizing it. It’s not a scary operation like

git rebase, it’s something everyone can do, so we can all look like geniuses in code review.

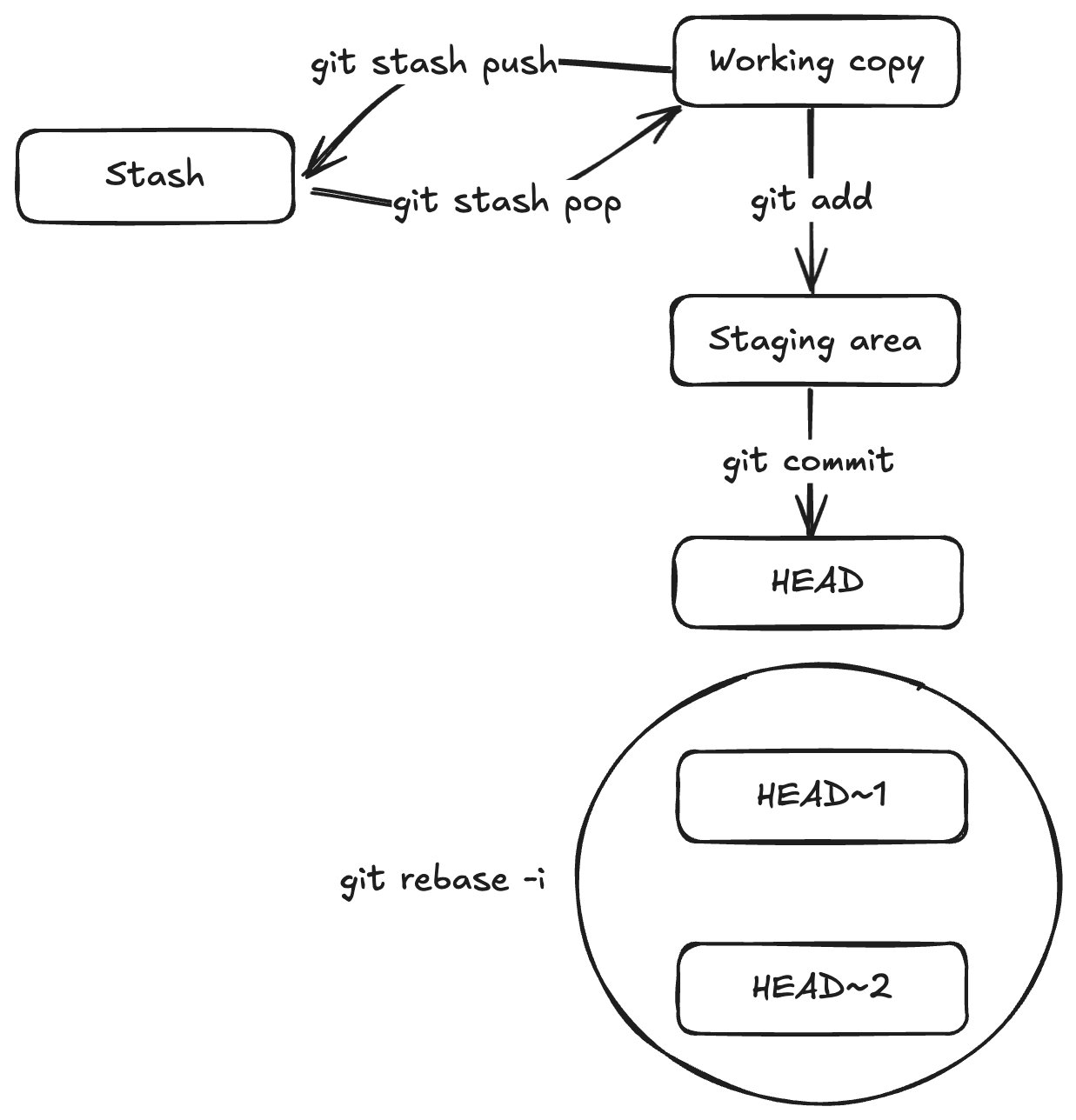

In Git you have the working copy, the staging area (AKA the index), the HEAD commit, and then all the commit history.

There are a lot of different commands you can use to move changes between these areas.

You have git add and git commit, but there’s also git checkout, git restore, etc., etc.

There’s also the stash, which has its own separate commands and flags.

And if you want to mess with previous commits, you have to use git rebase.

In Jujutsu, the working copy is the current commit. You make changes, and then whenever you run any Jujutsu command, those changes are automatically snapshotted into the current commit. That’s it. All the other Jujutsu commands are about manipulating commits.

Now if you’re like me, you might find this terrifying. I often make changes that I don’t want to commit, how do I avoid polluting my history with those?

In Jujutsu, you are usually working on a sort of work-in-progress “stub” commit. It can contain things you want to save and things you don’t. When you’re ready to call it complete, you create a new work-in-progress “stub” commit, and then you edit both commits, choosing which changes to carry forward into your new WIP commit, and which deserve to be saved in the history. In Git this would be a big scary operation, but in Jujutsu it happens by default.

Here’s one way Jujutsu makes it easy to rewrite history. You can switch to any commit and just edit it directly:

jj edit <commit ID>

Any changes you make get automatically saved into that commit.

What if you edit a commit way back in the history, and it conflicts with a commit later on?

Say your commit history looks like this, newest to oldest:

- Commit 3: rename

FootoBar - Commit 2: unrelated change

- Commit 1: unrelated change

Let’s say you run jj edit 1 and then rename Foo to Baz?

What happens?

In Git, you would be in a crisis situation. You would have to resolve the conflict immediately or else abort the whole operation.

But in Jujutsu, this is what you’ll see:

- Commit 3 (conflict): rename

FootoBar - Commit 2: unrelated change

- Commit 1: unrelated change

It simply marks commit 3 as conflicted and moves on with life. You can keep working on commit 1 and 2 and worry about it later.

When you’re ready, you can jj edit 3, open the conflicted file, and you’ll see something like this:

<<<<<<< Conflict 1 of 1

%%%%%%% Changes from base to side #1

-Foo

+Bar

+++++++ Contents of side #2

Baz

>>>>>>> Conflict 1 of 1 ends

Remove the conflict markers in your editor, run jj again, and you’re all set.

It even automatically resolves the conflict in all later commits in the history, unlike git rebase, which often makes you resolve the same conflict over and over in each commit.

How Jujutsu Works With Git

Git commits are immutable, so to “edit” one, you really have to destroy and recreate it.

It gets a new hash, along with every commit that depends on it.

That’s what git rebase does, and that’s what Jujutsu does under the hood.

In order to track the history of a commit over time, Jujutsu identifies it with a permanent “change ID” that (ironically) never changes, even when its hash changes.

Change IDs consist only of characters that cannot appear in a Git hash, so they’re always unique and easy to distinguish.

You can reference commits by ID or hash, and jj displays them both.

It also highlights the first few characters if they are enough to uniquely identify the commit. By the time I’m done with a pull request, I often know the commits by heart, since the IDs are so short, often just two characters:

jj edit yz

jj edit qu

# etc.

Typical Workflow

- Fetch the latest changes:

jj git fetch

- Start a new empty commit on top of the main branch:

jj new main@origin

Add some commits. Notice that you don’t create a branch. You’re actually never “on” a branch in Jujutsu. You’re just on a commit. Seems alarming, but you get used to it pretty quick.

When you’re ready to push, create a “bookmark”:

jj bookmark set -r @- my-branch

This is basically equivalent to a branch in Git, except if you add new commits, the bookmark stays put. You can manually set the bookmark on another commit, but it doesn’t happen automatically. More about this command in a moment.

- Push the new bookmark to Git:

jj git push --allow-new

Revset Language

Let’s look at that bookmark command again:

jj bookmark set -r @- my-branch

See the -r flag?

That’s us telling Jujutsu which commit to put the bookmark on.

This is an example of the powerful revset language Jujutsu uses to identify commits.

Here I’m setting the bookmark on @-, which is the commit just prior to the current one.

(Remember, usually the current commit is sort of a staging area. Jujutsu has some helpful blocks to prevent you from accidentally pushing this kind of commit.)

Like everything in Jujutsu, this language is highly orthogonal, meaning you learn a few building blocks and then wonder “can I combine them this way?” and the answer is yes. For example, I found myself wanting to do an experiment that incorporated changes from two different bookmarks.

The Jujutsu workflow starts with jj new, which, like most commands, accepts multiple revsets.

So I thought, can I make a new commit based on both of these bookmarks?

And the answer is yes:

jj new bookmark1 bookmark2

How It Looks To Everyone Else

Once you push your bookmark, it looks like a normal Git branch to everyone else.

Let’s say you need to fix some linter errors and test failures after pushing.

You can edit your existing commits and then jj git push.

It will appear to others as if you’ve rebased the branch.

If you have multiple bookmarks, jj git push pushes them all at once.

This makes it really easy to set up a stack of pull requests with one bookmark each.

You can make edits up and down the stack and jj git push to update all the pull requests at once.

Practical Advice To Get Started

If you want to try out Jujutsu, I recommend Steve Klabnik’s tutorial. The official docs are also quite good.

You’ll most likely want to use Jujutsu with an existing Git repo. Here’s how to do that:

jj git init --git-repo /path/to/repo

Some footguns to watch out for:

Disable all Git integration in your IDE. The official recommendation is to treat the Git repo as read-only. All write operations should be done through Jujutsu, not Git. If you do use Git to create a commit or something, Jujutsu does its best to sync itself with those changes, but it can get a little hairy. You might end up seeing changes in a “conflicted” state, where a single change is associated with two different commits. I found that VSCode does a lot of Git operations automatically in the background.

Submodules are unsupported and completely ignored by Jujutsu. I found this to be mostly fine in the monorepo at $WORK, but if you switch to a commit that has an added or removed submodule from where you were previously, things can get permanently screwy. To be fair, this isn’t that different from the normal Git submodule experience.

Good luck!