The Poor Man's Gameplay Analytics

You don't want to take time away from your awesome game to write boring analytics code. So you either call up some friends, hire playtesters, integrate some 3rd party SDK (ugh), or just do without.

WRONG. You roll your own solution. Here's why.

Why you don't do without

The OODA loop models the way human individuals and groups operate. It goes like this:

- Observe the situation

- Orient your observations in the context of goals, past experience, etc.

- Decide what to do

- Act on your decision

- Repeat!

After the initial act of creation, game developers operate under the same principle. You play the game and observe it, orient that data in the context of your goals, decide what to do, open your IDE, and put your plan in action. Rinse and repeat.

The problem is, unless you're a god-like game designer, your observations are fatally flawed, and there's nothing you can do about it. You're so close to the game that your view is wildly different from your players. You're sick of mechanics that should be fun. You breeze through sections that should be brutally difficult. Subtleties are blindingly obvious. Frustrating glitches are comfortable and familiar.

Your only options are to either reincarnate as Tim Schafer, or seek outside perspectives.

Why you don't hire playtesters

Easy: because you're broke.

Why you don't bring in friends

You can't trust yourself in this scenario. Here's how it always plays out:

You run into someone on the street. Maybe you know them, maybe not. Either way, you're about to monopolize their time.

You: Hey, want to playtest this game I'm working on?

Hapless victim: Um sure, I mean, I don't play video games much but

You: Don't worry, it's a procedurally F2P permadeath MOBA, you'll pick it right up.

Hapless victim starts struggling through tutorial. You hover behind them, watching and breathing heavily.

Hapless victim: This game is... cool. Very cool. Whoops! Died again. Haha. Hey I have to go to work/class/other vague commitment, but cool game! Very cool.

When you hand your game to a friend or stranger, you're saying "I think this is worthy of your time and I'd like to show it off to you." But the reality is, it's not (yet). It's incomplete and probably buggy. They try so hard to like it. You try so hard to convince yourself that they like it, but end up with hurt feelings anyway. Any useful data points you salvage from the wreckage are tainted by the fact that you were watching over their shoulder.

To solve these problems, you send a build to your close friend with instructions to ignore the bugs and placeholder assets, then breathlessly await their response. Maybe you get some useful feedback, maybe not. Either way, it's a big favor to ask of a friend, and you only get one new flawed perspective. Also, they're only a first-time player once.

Why you don't use third-party SDKs

Most third-party SDKs work great for F2P games where all you want to see are big-picture things like ARPU, retention, crash logs, etc. By all means, use them to get those numbers.

But to truly observe, you need to be able to watch over the player's shoulder without affecting their gameplay. Anonymously of course, and with their permission. You need to be able to record the whole gameplay session and play it back, and most third-party SDKs won't do that. The best way is to write analytics playback code directly into your game or level editor, because it already has the same code and assets.

One notable exception is GameAnalytics (if you're using Unity), which is free and offers 3D heatmaps right in the Unity editor.

Roll your own

It's the only remaining option. Send your build to friends, randos, whoever. No need to provide instructions, no awkward conversations. It's detached and impersonal, and you get exactly the data you need, because you wrote code to collect it.

What follows is my experience building custom analytics with not much time or money.

Implementation

It's easier than you think. For each gameplay session, there are three types of data you need to track:

- Metadata - timestamp, duration, version number

- Events - just a timestamp and an event name

- Continuous attributes - things you want to graph continuously over time, like player position and health

I use C#, so I shove this data in a class and serialize it to an XML file using built-in .NET functions.

Having one file per gameplay session makes it easy to move your analytics data around. If the player doesn't have an internet connection, you can retry later, deleting each file after uploading it to avoid duplicates, like this:

string url = "http://your-server.com/" + Path.GetFileName(file);

new WebClient().UploadData(url, "PUT", File.ReadAllBytes(file));

File.Delete(file);On the server side, I store these files in Amazon S3 for something like 50 cents a month. I don't want to give my S3 credentials to the client, so I have a dead simple Django app that accepts file uploads and uses boto to put them in my S3 bucket. It's hosted for free on Heroku. Here's the entire source code:

from boto.s3.connection import S3Connection

from boto.s3.key import Key

import boto

from django.conf import settings

import mimetypes

from django.http import HttpResponse

from django.views.decorators.csrf import csrf_exempt

def store_in_s3(filename, content):

conn = S3Connection(settings.S3_ACCESS_KEY_ID, settings.S3_ACCESS_KEY_SECRET)

bucket = conn.get_bucket(settings.S3_BUCKET)

k = Key(bucket)

k.key = filename

mime = mimetypes.guess_type(filename)[0]

k.set_metadata('Content-Type', mime)

k.set_contents_from_string(content)

k.set_acl('private')

@csrf_exempt

def upload(request, filename):

if request.method == 'PUT':

store_in_s3(filename, request.raw_post_data)

return HttpResponse(status = 200)

else:

return HttpResponse(status = 403)Wait for the sessions to roll in, download them from S3 (I recommend S3 Browser if you're on Windows), and load them into your game.

Results

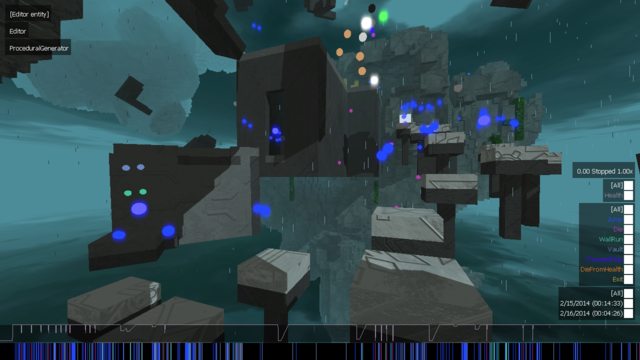

The UI is all custom, but it really wasn't too bad to write. On the right-hand side, I can view individual play sessions, or select all of them and filter by event type. For example, to see where people most often exit in a fit of rage, I can select all the sessions, then filter on the “Exit” event. The events appear on the timeline at the bottom, where I also graph the average of each continuous attribute (just health for now).

I also visualize player position at the time of each event as a 3D colored dot in the game world. I take the MD5 hash of the event name and normalize the first three bytes to generate the color. I can also play back the recorded sessions at up to 10x speed, and literally watch the position of each player as they go through the game.

The data collected has been invaluable for discovering things that no one will ever tell you in a feedback form. Things like "the second ledge on level 3 is a bit too high". In short, it's worth every second spent.

So. Go forth and measure!

If you enjoyed this article, try these: